Reflect, Reclaim, Redefine: Detroit's Imani Day Wants a More Diverse and Engaged Profession

By Sarah Rafson For most designers, it takes years to develop a distinctive style and purpose. Imani Day, a designer in Gensler's Detroit office, seems to be ahead of that curve. Imani, who earned her professional degree in 2011, has shown her strength as a designer through her work at Cornell and later in the offices of Robert A. M. Stern Architects and Diller Scofidio + Renfro. However, it was her move to Detroit that has helped Imani merge her interests in social justice with her design practice to encourage the architecture community to respond more aggressively to widespread urban problems.

In November, Imani participated in the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics’ symposium, Why Does Black Art Matter Now? at the University of Pittsburgh, where ArchiteXX editor Sarah Rafson spoke with her about her accidental discovery of architecture, the need for scholarship on women architects of color, and the non-profit she envisions to help reimagine the Detroit Public Schools through design.

SR: How did you become interested in architecture?

ID: I remember it very vividly. I grew up with my father who’s a visual artist, and my mother, who’s much more technical—she’s a writer and a teacher. I was always good at drawing and I leaned towards my dad quite a bit, but I wasn’t sure about being an artist, it seemed too risky. One summer in high school I went to the W.E.B. DuBois Scholars Institute at Princeton. At some point in a round table discussion we were asked to say what we wanted to do when we grow up. At the time I wanted to be a psychologist, but the last person before me to speak said, “I want to be an architect.” I remember thinking, "Wait a minute, that’s a much better idea!" I hadn’t been exposed to the idea before that—and that’s part of the problem. Not enough students of color are exposed early enough. It turned out that architecture was a great combination of what my parents do. If I had known, I would have been ready to dive in at six years old, I’m pretty sure.

The next summer I did a summer architecture pre-college program at Carnegie Mellon, and after that I started taking more classes. I worked with a mentor out of Newark who started pointing me toward Cornell.

Tell me about your experience at Cornell.

I loved Cornell, but it was pretty rough. When I started, I felt like was behind everyone else. It took me some time to get settled in. I noticed right away that there were not very many people there who looked like me.

Looking back now, I think that I was very smart, but somewhat uncomfortable in a Eurocentric, not-so-culturally sensitive curriculum. Cornell didn’t foster an aesthetic that responded directly to me. Overall, Cornell taught me a lot, but I often think of how different things would be if I went back to school now and could build on the aesthetic that is now important to me.

What is that new aesthetic?

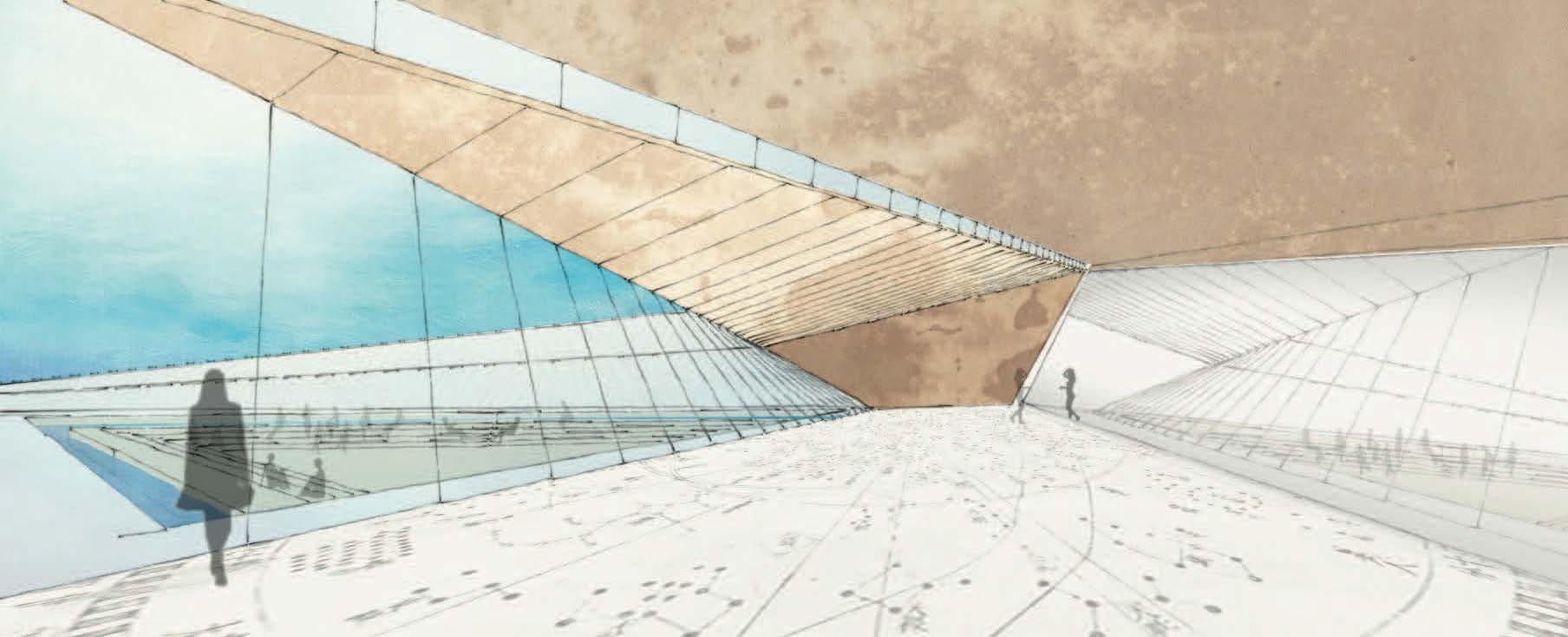

Actually, an intervention I designed in response to Robin Coste Lewis’ book of poems, Voyage of the Sable Venus (above), is a good example of where I’m heading with it. Part of the concept of the Voyage of the Sable Venus is about reclaiming your identity as a Black woman and digging deeper into the image of the Black woman as it has been historically portrayed. My project explains that it’s necessary to first reflect and acknowledge the images of us that exist and to then reclaim and redefine them. Architecture is very precedent-based, and I realized that there are not very many examples of strong, positive images of Black women in architecture to draw from. This project works on creating this image of strength but also a space that embodies that image.

As designers, it’s so important to define our history and self-image, because otherwise we don’t seem to exist. There’s not enough historical research on Black female architects. This project sent me into a hunt and I want to keep digging.

Who are some of the names you’ve come up with?

Some women of color in the US are killing the game in their own way, but none are as recognizable as Zaha Hadid. Diane Hoskins and Allison Williams, for example. Gabrielle Bullock is a really huge influence at Perkins & Will, Barbara Bouza at Gensler is also a really important figure, and Dina Griffin of Interactive Design Architects is another heavy hitter. My Detroit colleagues and mentors Kimberly Dowdell, Mitch McEwen, Tiffany Brown, and Devanne Pena are also forces in the industry who continue to motivate and inspire me. I think that these women have the potential to become household names. It’s been an important part of my career to identify, support, and mention these people to keep their make sure their names are heard.

There are a lot more women of color that I could name, just from the National Organization of Minority Architects' (NOMA) registry of people who are licensed. Still, I always think that tomorrow I’m going to find a Black woman architect who is recognizable, someone we can associate with a certain style or aesthetic, someone with some sort of notoriety, but I haven’t yet. The list of registered Black architects is still too short. It’s still so astonishing, and it’s not something I want to be astonished about in a few years.

Are you involved in NOMA?

Yes, I am currently secretary for the Detroit chapter. I think NOMA is a great organization. I was involved very lightly in college, but once I started to participate in NOMA as a professional it has helped so much. It’s a good part of the reason that I’m in Detroit. Kimberly Dowdell suggested I attend the 2014 NOMA conference in Philly right before I moved, and I met a young architect from Detroit named Tiffany Brown and told her that I was thinking of moving. I visited Detroit a week later and she introduced me to a group of awesome designers in Detroit, who really showed me the ropes and got me on board to feel strong about the decision to continue my career in the city. I ended up landing a great position as a designer in the local Gensler office, which is where I've wanted to work since I was a freshman in college. Now Tiffany and I are great friends and we’re studying for our licensing exams together.

I think it’s the NOMA attitude to go above and beyond to support each other. It has been a game-changing experience to be surrounded by people of color who share the same interests. The national conferences are by far the most motivating and inspiring things keeping me going. No matter how many people of color are in my immediate surroundings, I have a network of people who are right by my side via the internet or my phone. It reminds me why it’s so important for me to be in this profession.

I have become extremely passionate about reaching out to students in Detroit who may otherwise never be exposed to architecture. NOMA has a national program called Project Pipeline to introduce students of color to the design profession and educate them on the importance of the role of the architect. One of my Cornell Professors, Milton Curry, also runs a program called ArcPrep out of the University of Michigan, which selects various students from the Detroit Public Schools—students who may be facing challenging circumstances, to say the least—and exposes them to architecture and people who look like them. It introduces them to designers, real estate entrepreneurs, builders, and engineers changing their city for the better everyday. Both programs allow different types of people in the profession to show students what we do and cultivate the students’ interest, helping them develop their minds as designers, think creatively, and give them opportunities they wouldn’t have otherwise. Those programs are really important to me, because I wouldn’t be here without someone exposing me to the field. I think a lot of people of color in this profession can attest to why it’s important for NOMA to exist alongside the AIA.

How do you engage these issues in your practice?

As an architect, I’ve been very moved by the crisis of the Detroit Public Schools because so many of the system’s issues are physical, architectural, mechanical. Gensler has a relationship with City Year to help renovate schools one space at a time, but I want to dig deeper. I’m definitely not ready to quit my job or anything, but I sometimes dream about dropping everything and starting a nonprofit to truly revamp these schools! You can’t flourish, you can’t learn, you can’t focus if you have to wear your coat all day because there’s no heat or you’re inhaling mold or entire classrooms have flood damage that won’t be repaired or the lights may not come on, or any of the other obstacles kids face at school everyday. I felt behind when I got to Cornell and I went to perfectly fine public schools for most of my life, so it’s hard ignore this major problem facing Detroit’s schools in the grand scheme of education.

I feel a very strong responsibility towards this crisis. I wish the state of public schools in this country were a more widespread focus and obligation to our profession. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t be spending a lot of energy and effort to help build the next generation of people who will undoubtedly be designing our built environment. The more people we reach at the high school level, the more students we will have studying architecture—and we know how few students of color there are graduating from architecture school. It seems like such a simple formula to address such a tough reality. So hopefully the next time we talk I'll be telling you about my more concentrated effort, possibly called Design DPS, to help re-imagine Detroit’s schools! I feel very passionate about this. I have really sunk my teeth into Detroit, I am so moved by the energy there.

I will hold you to that! How does this play out in your work at Gensler?

Part of the reason I’m so obsessed with the school system is that as architects I think it’s our first job to serve our communities and listen and see what the needs are. We’ve had some really inspiring charter school work in our local office with the Detroit Achievement Academy, which really sparked my interests in digging deeper into the city’s school system. Listening to the clients’ needs was not necessarily a major part of my experience or training in New York. I’ve always wanted to help people who need specific things and resources, not necessarily just want something new. Gensler is a very workplace, retail-oriented office and I believe part of my role there is to explore different opportunities at the community level in Detroit. As the largest firm in the world, Gensler has the opportunity to—and really has helped—bridge the gap between major, global, corporate vehicle mentality and local, community level needs. Detroit doesn’t need a prescribed, jargon-filled, predictable response—I think our smaller Detroit office can offer a less conventional route through more guerilla-style interventions. That’s where my interests lie within Gensler and in the city of Detroit. I’m excited to see how the two can blend.

Is it fair to say that Detroit is helping you become the type of architect you want to be?

Absolutely. I was actually very against moving to Detroit before visiting and having Tiffany and other people help me fall in love. As a young designer I was bottom-feeding in New York and barely surviving on a number of levels: energy, money, happiness. I won’t say that my Detroit experience is any easier, but I’m happier. My potential is much more actualized in Detroit. The city has so much work to do that young designers, critical thinkers, writers have the ability to make a huge impact. There are a lot of startups, there are a lot of entrepreneurs, a lot of innovative people who want to develop the city—they’re not always working on the most glamorous projects but they creatively respond to very tight budgets and they’re so impactful. Suffice it to say that I have become one of the biggest cheerleaders for Detroit right now.

I’ve been a lot more stimulated as a designer in Detroit. It’s hard for me to believe that I would have come up with any of these ideas in New York because I would have been so busy, so sleep-deprived. That’s not to say that my experience working in New York was not valuable. I am the designer I am partly because of who I worked under: Robert Stern, Liz Diller and Ric Scofidio—they are not a small part of my design style and thought. But my autonomy and my ability to think and design independently of them and develop my own style has really happened in Detroit.

In New York, I felt really good about the projects I worked on because they were provocative in terms of design, but you can be provocative through design at the community level, where it’s even more important because it doesn’t happen enough. For me, that’s where it really all has to start. Coming to Detroit really allowed me to take risks and to connect to the profession in a completely different way—and for that I am incredibly grateful and looking forward to what becomes of this new venture.

Sarah Rafson is an editor of sub_teXXt and serves on the board of ArchiteXX. She recently founded Point Line Projects, an editorial and curatorial agency for architecture and design.