Young Architects Respond

Millennial architects explain the real reasons we won’t be your CAD bitch. By Violet Whitney, Julie Pedtke and Matthew Lohry

[above: Poolside millennials revelling in “the freedoms that youth affords.”]

Young architects, seen as politically self-important millennials, too “impatient” and “entitled” to work their way up the ladder, are rejecting jobs at brick and mortar architecture firms in favor of more immaterial and temporal work. Research grants, pop-up pavilions, and other short-term jobs within the gig-economy have become mainstays for jump-starting a career. In their thinkpiece published by The Architectural Review, “The Problem with Young Architecture,” Phineas Harper and Phil Pawlett Jackson lament the culture of young architecture that is celebrated and legitimated by awards like the “Young Architects Prize.” According to them, young architecture has commodified DIY modes of practice, limiting the ability of rising practitioners to move on to larger commissions or gain financial support. They reminisce about a time when medium-sized firms comprised a healthy ecology of practice, and warn of the detriment that young architecture poses to the profession.

As students at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, we find these attitudes towards young architects unwarranted and out of touch. We feel the need to respond from our own perspective and highlight the many conditions intrinsic to the phenomenon of young architecture.

We are not the “trust fund recreational class.” Practicing young architecture—“socially high-risk, financially low-return”—is often our only option. It is not a choice to “revel in the freedoms that the privilege of youth affords” (six-digit student debt hardly invokes a feeling of freedom, after all), but a strategic response to the lack of options available to young practitioners. There is an urgency within our class at Columbia University to distinguish our ambitions from those of practitioners who have come before us, and to contextualize young architecture by calling out Old Architecture for what it is.

Old Architecture (statistically cis male, white, and wealthy) has failed to lead the social, economic, and technological changes that are demanded by growing societal inequalities. It has upheld exclusive hierarchical traditions, reproduced the values of its wealthy white clients and practitioners, and supported repressive economic policy. It is these conditions that have led to our current state of environmental and financial precarity, in which competition for underpaid entry-level positions combined with massive student debt make it increasingly impossible to continue in the manner of our predecessors even if we wanted to. Old Architecture is not only inaccessible, but for both economic and ethical reasons it is not worth pursuing.

The values of Old Architecture—the myth of the creative genius at the head of the firm, the continued preference for the labor and leadership of men and the undervaluing of the same labor by women, the trivialization of community involvement, and the lack of attention to ecological concerns—have long been absorbed into our magazines, our schools, our firms, and into the culture of our profession. If in pointing to these shortfalls we seem to be exacerbating the “divisive demographic antagonism” Old Architects warn against, we would like to point out that this antagonism already exists in other forms: antagonism towards young practitioners, women, people of color, LGBTQ+, and low-income communities.

Forced to think creatively in the face of our own financial instability, we cannot help but question the fundamental role that capital plays in the production of architecture and urban space. A critical discourse addressing capital is curiously absent from our academic programs (which are defined not by young practitioners but by established accreditation boards and university administrations). Students are instructed to pretend that money does not exist, even in a time when the financialization of the economy, privatization of resources, and growing wage inequalities put increasing strain on the profession. We have yet to view the constraints of our economic system as a realm of productive creativity, worthy of inclusion and critical discussion. While there are benefits to allowing students space to explore and develop free from “practical” concerns, an active exclusion of economic forces can result in architectures limited to their conceptual frameworks, and evaluated based on arbitrary formal qualities.

There is perhaps a place for purely aesthetic, formal experimentation within our cities, but it would require an abandonment of the pretense of social relevancy. Too often the aesthetic disguises another form of commodification, that of unavoidably expensive Starchitecture. The normalization of this practice limits the potential of architecture beyond the ultra-luxury marketplace.

If we hope to regain value in the eyes of the public, we need to be sincere about what we are offering. Do architects provide a service that addresses local needs and directly improves the lives of inhabitants, or a luxury object that will attract tourists and investors? Can we do both, or do these agendas often directly contradict each other?

There is room for both in the profession, but distinctions must be made. More and more young architects are moving away from luxury architecture, acknowledging the complex, interwoven mechanisms in our global economy and the need to invent our own means of engaging systems of production. We partner with developers, collaborate with business students, or work in the nonprofit sector to learn alternative fundraising. We are developing alternative forms of practice based on the acknowledgement that our specialized spatial knowledge is strengthened by diverse partnerships, and that to have a permanent impact we must to address the outdated accreditation and professional organizations that young practitioners work within. There needs to be a recognition that our rigid curriculum and licensure processes represent only one insular slice of a larger world of information, technologies, methodologies, ethics, and analysis that should be included in architectural practice.

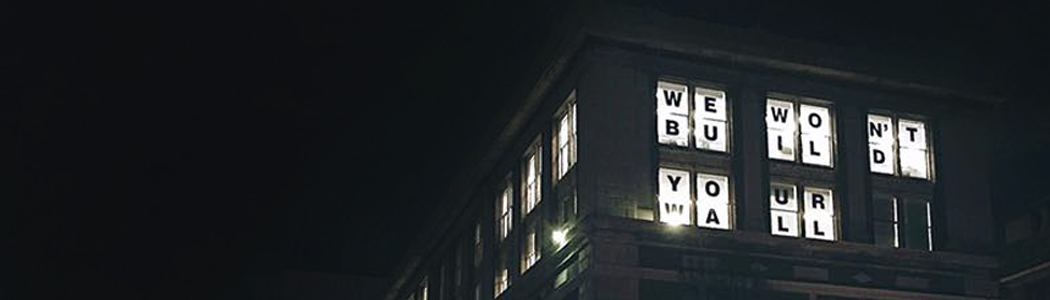

We are young, and we lack experience in the field and the perspective this affords. However, we cannot continue to operate on the fallacy that we will succeed in a rapidly changing economy by following in the path of those who have come before us. To be complicit would only exacerbate the conditions that generated the inequalities in the first place. Competing for politically unsavory contracts just to maintain a business is a short-sighted economic imperative that needs to be transcended by designers coming together as a profession. Dehumanizing architectures such as poor doors, border walls, private prisons, and binary bathrooms are not a way out of economic instability and increasing inequalities. Students and young practitioners are in a position to call out injustices and refuse to assimilate to a flawed profession. We are now signaling to firms that hope to woo young talent that we "won’t build your wall" and will not join an office that considers such contracts.

Rather than dismissing young architecture as limited to trendy awards and ineffective pop-ups, our work should be understood as building a community of allies and alternative practices to confront the role that capital plays in the profession and seek to undo its exclusionary traditions.

Violet Whitney, Julie Pedtke and Matthew Lohry contributed this article on behalf of A-Frame, a cooperative platform for young architects to share resources, incubate projects, and engage with alternative forms of practice. A-Frame invites you to get involved with the many young organizations tackling the issues addressed in this article, including our friends below:

- http://architecture-lobby.org/

- http://qspacearch.com/

- http://www.nonscandinavia.com/

- http://madeinbrownsville.org/

f-architecture (alt: feminist architecture collaborative) is a three-woman research enterprise aimed at disentangling the contemporary spatial politics and technological appearances of bodies, intimately and globally. Partners/caryatids/bffs Gabrielle Printz, Virginia Black and Rosana Elkhatib run their practice out of the GSAPP Incubator at NEW INC, an initiative of the New Museum.